Contributed by Jennifer Wong-Ala

Contributed by Jennifer Wong-Ala

The aroma of freshly defrosted Alepisaurus ferox (Longnose Lancetfish) stomach begins to fill the lab as I place my first stomach of the day on the dissection tray. I look at the unopened stomach and begin to see an odd shaped object protruding from the inside. I make my first cut to expose the stomach contents and see the culprit responsible. A white piece of plastic that closely resembles the material paint buckets are made of emerges along with a degraded piece of a black trash bag intertwined with fishing wire. I begin to shake my head and continue to document the rest the of stomach contents.

Plastic pollution has been known to affect large, much-adored marine animals such as sea turtles, monk seals and seabirds. These animals can be strangled, suffocated, or even killed when they ingest plastic debris. Even microscopic organisms such as copepods have been seen to eat microplastics because they closely resemble phytoplankton – microscopic plants in the ocean. Now teams of scientist from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UHM) are finding more trash at deeper depths (2000 – 4000 m), where commercially important fish are mistaking plastic debris as food.

But how does plastic even get that deep in the ocean? Aren’t most plastic debris buoyant and stay on the surface? Scientists at MBARI analyzed 1149 video recordings of marine debris from 22 years, looking at videos from remotely operate vehicles (ROVs) in the Monterey Canyon, and found that the largest proportion of the debris observed in the videos was plastic (33%) and metal (23%). Plastic debris was most abundant in undersea canyons at depths of 2000 to 4000 meters. It is thought to have reached those depths by these canyons’ natural sediment transport processes, which exert forces great enough to carry research equipment to the bottoms of these canyons.

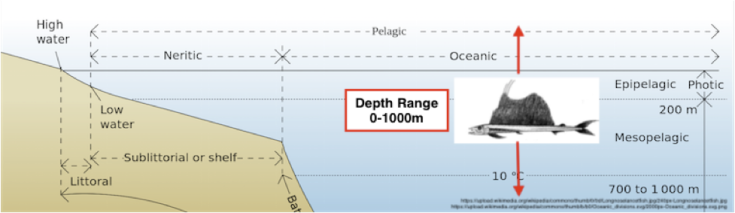

Plastic debris can also be passed through the food web in the ocean when deep-sea animals eat other organisms that can live at many depths. For example, plastic debris has been found in the stomachs of the lancetfish which occupy a broad depth range (0 to 1,000 meters). Lancetfish have been found to ingest plastic from the surface and then travel to deeper depths where it becomes prey to other species such as Opah, Albacore and Yellowfin tuna. The plastic from the Lancetfish has now been passed through the food web and potentially to our dinner plates.

Big steps are already being made in regards to one type of plastic debris called microbeads. This year President Obama signed the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 that will ban the use and sale of products containing microbeads by 2018 and 2019. This was a big step in making a positive impact for our environment, but there is so much more to do.

Jennifer Wong-Ala transferred from Kapi‘olani Community College to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UHM) in Fall 2015 as a Junior in the Global Environmental Science Program. She is a NOAA Hollings Scholar, C-MORE Scholar in Dr. Neuheimer’s Lab, Laboratory Technician in Dr. Drazen’s Lab, and is also part of the SOEST Maile Mentoring Bridge. Jenn is interested in computer modeling/analysis of how ocean processes interact with organisms in the ocean and how to best preserve these natural resources. In the future she plans to bring these skills and interests together to conserve marine life in Hawaii. This post was originally written for OCN 320 (Aquatic Pollution), a writing intensive requirement for the GES major.

Leave a comment